INTRODUCTION

This paper focuses on graduate students’ experience with the completion of a research project relating to mental health under the guidance of their ‘facilitative’ supervisor. The research process was designed to enable the students to move towards an interrogation of qualitative material; to appreciate the value of inquiry and critical thinking and interpretation of evidence around a challenging topic reported on by contemporary media in Japan. They were encouraged to reflect on the impact on their assumptions about mental illness and distress. In this paper supervisor and students share the results of their research and experience of this process.

Background

Numerous studies have documented an association between negative media portrayals of people with mental health disorders and negative attitudes and stigmatization have been associated with influencing suicide. However, this research has not been well developed in Japan. Suicide is one of the leading causes of death worldwide with Japan having one of the worlds’ highest rates of suicide: the depiction of suicide in the media can negatively affect suicide rates. Researched in this study are the frequency with which mental health and suicide are mentioned in three major Japanese newspapers and the tone and content of this coverage.

This was worthy of critical analysis by students and was the focus for students enrolled in a research subject. This paper reports on the learning processes and the study undertaken by the students led by their facilitator. The students explored what was involved in reviewing the literature and, together with the supervisor decided what topics were relevant to explore and how this should proceed. As a team we discussed how our assumptions may impact the study design and findings and listed these. We held certain assumptions - that

• there would be few articles in Japanese newspapers about mental health

• stress would be frequently mentioned

• mental health reporting would be negative in tone and include stigmatizing elements

• there would be an assumed association between and mental illness and aggression

• suicide may be presented in ways that do not align with the WHO guidelines for responsible reporting.

Before looking at the role of newspaper reporting students explored the literature on suicide, stigma and mental health treatment and the role of the media in relation to stigma in Japan, then reflected on the significance of the topic before designing and undertaking the study.

Suicide

Japan has the unfortunate reputation of having a high suicide rate and suicide is a major public health concern (Ono et al., 2008): 3-5 times more people die from suicide in Japan annually than die in road traffic accidents (Targum & Kitanaka, 2012). The age 35-49 cohort of those with mental health disorders are at highest risk of both suicidal ideation and attempts. Others at high risk are those in the period after initial employment (Ono et al., 2008). The suicide rate in Japan increased to over 30,000 a year after the economic crisis in the late 1990s (Russell et al.,2017).

Undoubtedly cultural factors contribute to the high rates of suicide especially in a culture where social cohesion is important; shame and social isolation are used to maintain social cohesion (Davies & Ikeno, 2011; Russell et al., 2017) and historically suicide was seen as the ultimate form of self-sacrifice and was used as a means of maintaining social order (Russell et al., 2017) and suicide was seen as an honorable act (Ikunaga et al., 2013). Suicide was once normalized in Japan as an act of free will but high rates of suicide have changed this conceptualization towards it being a result of a mental health problem (Targum & Kitanaka, 2012). Although rare in Japan today, the concept of kakugo no jisatsu or premeditated suicide, a way of creating meaning through one’s own death, was cited in the media and popular fiction as a rational way of taking responsibility for one’s own actions or protesting against injustice (Targum & Kitanaka, 201). This conceptualization of suicide has mitigated against people seeking help from mental health professionals because there was a view that medicine should not interfere with “irresolvable aspects of patient’s lives” (Targum & Kitanaka, 201). Possibly unique to Japan is the concept of karo jisatsu “overwork suicide” as a result of too much pressure coupled with depression and a sense of being overly-responsible (Targum & Kitanaka, 201). Changes in workplace legislation have been enacted to deal with this.

Disturbingly, suicides in particular places, such as the infamous “suicide forest” Aokigahara Jukai and in particular ways. Suicide rates rose with the publication of the self-proclaimed suicide liberalist Tsurumi’s (1993) Complete Suicide Manual (Roarty, 2013), a matter of fact guide on how to suicide which was easily available at convenience stores and sold over a million copies and is still available online.

Conversely an overemphasis on the cultural components of suicide and the uniqueness of Japanese culture simplifies the situation in contemporary Japan (Ikunaga et al., 2013). Although the media tends to concentrate on the more newsworthy acts of suicide such as internet suicide pacts, suicide seen as a result of bullying and suicide of isolated people, in common with other countries many suicides have their basis in economic problems and unemployment (Matthews, 2008).

Although suicide rates in Japan are high, the prevalence of mental health disorders is apparently lower than in the USA and most European countries but comparable to China (Kawakami et al., 2005). Only one in five with a serious mental health disorder sought treatment (Kawakami et al., 2005). Globally the prevalance of mental health disorders may be related to people not seeking help because of the stigma of mental health problems; not rerporting symptoms because of stigma; current diagnostic tools, such as the ICD and the DSM, may not accurately evaluate disorders in Asian countries or concerns about disclosure (Clement et al., 2015).

The Law Related to Mental Health and Welfare of the Person with Mental Disorder in Japan (Shiraishi & Ohi, 2006), defines mental health disorder as involving “a person or persons suffering from schizophrenia, acute poisoning of or dependence on psychotropic substance(s), mental retardation, psychopathy or other mental illnesses” (Shiraishi & Ohi, 2006). Under this law, psychopathy or other mental disorders include every mental health disorder listed in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) F00~F99. All of these disorders can feature in learning materials but a high proportion of people (80%) with mental health disorders in Japan do not receive treatment (Naganuma et al., 2006), perhaps because of high levels of stigma (Desapriya & Nobutada, 2002).

Mental health treatment in Japan

Japan has in place a national mental health policy and this was most recently updated in 2009 and mental health legislation was last revised in 2005 (World Health Organization, 2011). The number of people with mental health disorder who receive treatment or medication from health services has increased significantly from 3.92 million in 2014 to over 4 million in 2017 (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2020). Included in this figure from most to least prevalent are depression, schizophrenia, anxiety disorder and dementia. Recently, the number of people diagnosed with depression and anxiety disorder has markedly increased (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2020).

Stigma

Stigma is a mark of disgrace associated with a particular circumstance, quality, or person that discredits a person (McGinty et al., 2019). People with mental health disorders frequently encounter public stigma and may also suffer from self-stigma (Corrigan et al., 2010). A systematic review of the literature relating to mental health stigma in Japan between 2001 and 2013 concluded that there was significant stigma related to mental health disorders. The general public generally believed that people with mental health disorders were unlikely to recover and that illness was related to personality weakness (Ando et al., 2013). Japanese people tended to keep a further social distance from those with mental health disorders and that stigmatizing attitudes were stronger than in Taiwan or Australia (Ando et al., 2013). However, this research is now dated, and attitudes may have changed in the interim.

The research team acknowledged that there may be cultural aspects to stigma in Japan. Japanese values stress harmony and conformity (Omura et al., 2018) and perhaps the difference in stigma might be mediated, by the differential value placed on conformity and individualism (Griffiths et al., 2006) between Australia and Japan. It is also likely that the long length of stay in mental health facilities contributes to stigma because people are less likely to come in contact with people with mental health problems (Griffiths et al., 2006) and contact is known to decrease stigma. Anti- stigma initiatives can improve help-seeking behavior and reduce the burden of mental illness on both individuals and society (Kasahara-Kiritani et al., 2018).

We concluded that depiction of suicide in the media had the potential to negatively affect suicide rates and set out to explore the frequency with which mental health and suicide are mentioned in three major Japanese newspapers and the tone and content of this coverage. Numerous studies have documented an association between negative media portrayals of people with mental health disorders and negative attitudes and stigmatization and has been associated with influencing suicide, but this research has not been well developed in Japan. Suicide is a major learning focus for programs preparing health professionals for mental health practice.

Newspapers in Japan

Japan has one of the world’s most literate populations with only-2-3% unable to read or write (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology-Japan, 1959) and Japan’s top three national newspapers are ranked the highest in the world in terms of print circulation (Jung & Villi, 2018;Rausch, 2012;Chen, 2015) (Table 1).

Newspaper circulation in Japan rapidly increased between1920~1930 with a threefold increase between 1920 and 1930: the increase has been attributed to incomes increasing during and after the first world war, rapid industrial development and needs for information about politics, economy and society, and expansion of people’s sphere of action (Kase, 2011). There are currently three major daily newspapers (shimbun) in Japan: Yomiuri Shimbun (2020), which has the largest circulation (Table 1), was founded in 1874; the Asahi Shimbun, is considered the most prestigious and was founded in Osaka in 1879; and the Mainichi Shimbun (Rausch, 2012). Yomiuri Shimbun is identified as a more conservative newspaper or right-leaning paper than Asahi Shimbun and (Jung & Villi, 2018;Ottewell, 2017). Readers of Asahi tend to be white-collar with higher educational backgrounds whereas the other two papers have a higher proportion of blue-collar workers or people without an occupation (Ottewell, 2017).

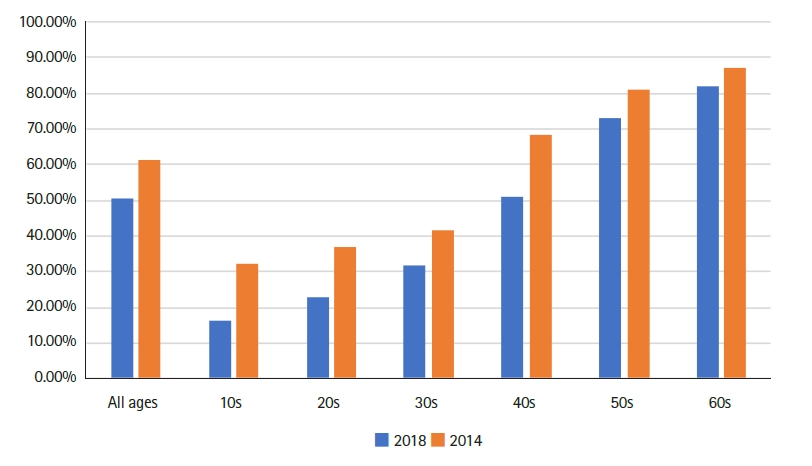

A high level of newspaper readership compared to the global average may in part be because Japanese people consider newspapers to be a more credible source of information than television or the internet (Chen, 2015). Newspaper subscription rates vary across age groups with older people more likely to subscribe than younger groups (Figure 1): Two-thirds of parents having children under 12 years old do not subscribe to any newspapers and half of these have never subscribed.

Following a literature search of English and Japanese publications, we concluded that there was little research in Japan on media and mental health. While there have been studies in Japan about the suitability, and health content of cancer screening information in newspapers in Japan (Okuhara et al., 2015) to our knowledge there has been no recent research about the coverage of mental health and suicide in the Japanese media or how that might mediate stigma. Ottewell (2017) examined the three major Japanese newspapers coverage between 1987 and 2014, and found there was reporting of mental illness in relation to stress than in relation to dangerousness but schizophrenia was often reported in the context of violent crime. Information on the treatment, symptoms and prevalence of mental illness was rarely reported. Ottewell did not examine media coverage in relation to reporting guidelines and called for more research in this area. A preliminary study of newspapers and the internet between 1987 and 2005 examining the association between internet use and suicide reported that the number of newspaper articles about suicide was a predictor of suicide among both males and females in Japan (Hagihara et al., 2007). The authors also found that internet use influenced males more than females, perhaps because males spent more time online, and was also a predictor of suicide for males. In our study we chose to analyse coverage of mental health issues in the online content of Japan’s three major newspapers because of the high proportion of newspaper readers in the Japanese population and of the reported high levels of trust readers have in the veracity of newspaper coverage. In addition other research has established that newspapers are the most frequently identified source of mental health information (Stuart, 2006).

This research therefore also addresses limitations in previous studies on media coverage of mental disorders: unlike Coverdale et al. (2002) we did not rely on an external body to conduct the search in order to ensure that we obtained a complete record. Other cross-cultural studies, for example (Dzokoto et al., 2018;Thornicroft et al., 2013) cross-cultural studies did not conduct pilot studies or consult an expert panel regarding terminology. Most studies of media coverage of mental health have used broad definitions of mental health (Knifton & Quinn, 2008) but we precisely identified the types of disorders and search terms.

Research Goals

The main goals of our study were to determine how many articles on mental health disorders were published during the defined period; how suicide and mental health disorders were portrayed by the major newspapers in Japan and examine the tone of the articles in regard to stigmatization of people with mental illness. Secondary goals included examining the source of information published; the types of mental disorders presented; and whether aggression was associated with people diagnosed with mental disorders.

METHOD

The research team explored the concept and the evidence of frequency with which mental health and suicide are mentioned in three major Japanese newspapers and the tone and content of the coverage.

We used an exploratory descriptive study i) using purposive sampling of the three Japanese newspapers with the widest circulation (Asahi Tokyo, Yomiuri and Mainichi) and ii) document analysis reliant on 37 keywords relating to mental illness iii) selected after consultation with a range of mental health experts across Japan. The national morning editions of the newspapers were searched by graduate students for a six-month period from 1st January 2020 to June 30, 2020 (182 days) and totals of the 37 keywords recorded. The articles were also coded for the types of disorders named and described and for the sources of information about mental illness, such as inclusion of perspectives from mental health experts, persons with mental disorders, or their families. Disorders that were included corresponded to classifications from the International Classification of Diseases 11th revision (World Health Organization, 2020)

Search Terms

The final list of search terms in English was: Affective disorder, aggression, alcohol-dependent, anorexia, anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, bulimia, depressed, depression, eating disorder, mental, mental disorder, mental health, mental hospital, mental illness, mood disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), panic disorder, personality disorder, psychiatric, psychopath, psychotic/psychosis, PTSD, schizophrenia/schizophrenic, social anxiety disorder (SAD), social phobia, stress, suicide/suicidal/self-killing, self-death. Adjustments were also made to Japanese terms to reflect feedback.

Only articles related to mental health disorders were included. Search terms were identified by the primary researcher an experienced teacher and Australian mental health professional. Disorders included generally corresponded to the International Classification of Diseases 11th revision (World Health Organization, 2020). These terms were then translated into Japanese. The translation and backtranslation process and consultation revealed several issues. Terms such as substance misuse and substance abuse translated into the same words in Japanese. In 2002 Japan, the name of schizophrenia was changed for the purposes of stigma reduction, from Seishin-Bunretsu-Byo (mind-split disease) to Togo-Shitcho-Sho (integration disorder) (Koike et al., 2016) but these two terms translate into the same term in English. ‘Suicide’ has additional terms such as ‘self-killing’ and self-death’ in Japanese. “Self-killing” has connotations of doing something wrong whereas self-death does not include killing and indicates that the person wanted to live but had no choice but to die because of social or economic reasons. This list in both English and Japanese, was then sent to several specialists in mental health across Japan and comments invited. These specialists included a Tokyo-based psychiatrist specializing in trauma; three professors of mental health nursing from Yamaguchi, Kanazawa, and Kyoto respectively; a mental health clinician and two mental health clinician/academic. Following discussion, to contain the scope of the project, drug use and substance misuse was omitted given many false positives. Another term excluded after pilot testing over 26 weeks showed no ‘hits’ for borderline personality disorder.

Search Strategy and Data Collection

Purposive sampling of the national morning editions of the newspapers occurred following a small pilot study in which the Nawka et al (2012) all newspaper parts were searched: news, interviews, columns, and editorials and data recorded over six-months from 1st January to June 30th, 2020.

Analysis

Keywords were analysed by the student researchers as part of their PBL learning using simple descriptive statistics (frequency and percentage distribution) and articles were then analyzed for stigmatizing content using predetermined codes following Rhydderch et al. (2016) which included article type, tone of coverage, focus - international/national, mention of aggression or method of suicide and whether there were elements of responsible reporting such as links to sources of help and information.

Trustworthiness

All decisions were documented by email and during discussions between students and supervisor. Confirmability was ensured by maintaining an audit trail, of each step of data analysis. To maximize consistency between coders, education was provided and formal meetings were held to cross-check responses and clarify the use of definitions and criteria (Francis et al., 2004). Inter-rater reliability was assured through content analysis by two independent researchers. Differences were discussed with a third researcher.

RESULTS

Data collection involving electronic searches proceeded as outlined above. All parts of the newspapers were searched for key words, including news, interviews, columns, and editorials.

In total over the six months period the overall count of the selected keywords was 1875. ‘Stress’ was by far the most frequently mentioned term at a total of 740 times over the six-month period, that is an average of 4.1 times a day. Other frequently mentioned keywords included suicide/suicidal/self-killing (n=452), mental disorder (n=80) about which there was an average of 0.44 articles a day, mental illness (n=69) with an average of 0.38 articles a day, depression (n=93) and psychotic/psychosis (n=42). There were few mentions of some mental health disorders including personality disorder (n=6) and eating disorder (n=5).

There were no mentions of some mental health disorders including affective disorder, social phobia, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and bulimia.

Looking in more detail at four selected keywords mental disorder, mental illness, mental illness (informal) and psychiatric, the overall count of these keywords was 172 with ’mental disorder’ by far the most frequently mentioned term at a total of 77 times over six-month period. The vast majority (n=168) 97.6% of the articles related to national news. Regarding the type of article 70.3% (121) were news and 29.7% (51) were opinion.

Most of the coverage was neutral in tone (86.6% n=149) and positive, with only eight (1.2%) articles classified as negative or stigmatizing. Of those articles which mentioned suicide one concerned an attempted suicide, 11 related to completed suicides, and six were about suicide in general. The method of suicide was reported only once but in a great deal of detail. Only 5.2% (n=9) of the articles, all of which were about suicide, included a link to help and information.

DISCUSSION

Our study provides substantial information about the extent and characteristics of newspaper portrayal of mental disorders in the three main Japanese newspapers over a six-month period. Broadcast and printed media are considered to be the public’s major source of information regarding mental health (Nawková et al., 2012). Mental health and illness were the subject of 1875 articles in the three newspapers over the six-month period of the study. The extent of this coverage was unexpected. ‘Stress’ was by far the most frequently mentioned term at a total of 740 times it is likely that this is related to the reporting period including the opening months of the COVID 19 pandemic and its associated health and economic impacts. The other keywords for which there were the highest number of mentions were mental disorder (80), mental illness (69), depression (93), psychotic/psychosis (42).

In contrast with previous research in the UK (Chen, M. & Lawrie, 2017), Europe (Nawková et al., 2012), India (Armstrong et al., 2018) and New Zealand (Coverdale et al., 2002) we found that newspaper reporting on mental illness was overwhelmingly written from a neutral standpoint (86.6%). This accords with an Australian study (Francis et al., 2004) who found that “media reporting of mental health/illness was extensive, generally of good quality and focused less on themes of crime and violence than may have been expected” and another British study (Thornicroft et al., 2013) suggesting that stigma of mental illness is unlikely to be formed by newspapers. The importance of this study's results is that one type of media, newspapers, are less likely to be agents of stigmatization of suicide. The latter may be occurring in other ways in Japan. Based on this result, it is necessary to examine other media in the future to appreciate which media provide mechanisms of stigma.

Suicide

Suicide, suicidal or self-killing was the subject of 442 articles over a quarter (26.6%) of the total articles involving mental health. Other authors have noted that suicide is extremely newsworthy in Japan (Matthews, 2008). Tragically over the six-month study period 9468 people in Japan took their own lives, that is on average 55.4 per day and this is up 16% from the same period last year (National Police Agency, 2020). In October 2020 there were 2,153 deaths by suicide and that was the fourth month of increase (Craft, 2020). This rise is also likely to be a result of the COVID 19 pandemic. While Japan has managed the pandemic more effectively than other nations it is likely that job losses, increase in domestic violence and uncertainties have had profound impacts on mental health (Craft, 2020). Japan reports suicides more rapidly than other countries and it is likely that COVID 19 will increase suicides across the globe.

The high levels of reporting of suicide reinforce the need for responsible media reporting to mitigate any adverse impacts or “copycat” suicides as well as providing links to help and advice. Concerningly a Japanese study found that the number of newspaper articles about suicide was a predictor of suicide among men and women (Hagihara et al., 2007). Media guidelines have a verifiable impact on the quality of reporting on suicide and, it is estimated that guidelines can prevent more than 1% of suicide deaths (Sinyor et al., 2018). The World Health Organization suicide reporting guidelines state that the suicide method should not be reported and neither should a public site be named as location of a suicide death/attempt (Chang & Freedman, 2018). In addition, negative life events presumed to have led to the suicide, such as debt should not be used as monocausal explanation and details of any suicide note should not be revealed. It is also advised that the reporting should not be accompanied by a photograph and the word suicide should not be in a headline. In contrast it is helpful to note link between suicide and mental health disorders, dispel common myths and provide links to support.

Limitations

The strength of this study is that three newspapers with the largest number of subscribers in Japan were used. The taboo nature of suicide, legal considerations and guidelines about reporting death, lead journalists to use euphemisms or other expressions that are not captured by our search and thus we may have underestimated the number of articles published. As in most media research results may not be generalizable beyond the media sources selected for study. It is also acknowledged that readership of newspapers may be skewed towards older age groups and that younger people may not constitute a high proportion of readers although the content analyzed was all available online. A limitation which is perhaps unique to Japan is that journalists from the three papers may have been at the same briefing at the press clubs and therefore the coverage is not independent.

Implications

Strategies which have been suggested to increase the quality of mental health reporting include the inclusion of mental health into undergraduate curricula (Skehan et al., 2009); consulting with mental professionals over content (Dzokoto et al., 2018); Stigma Watch and Media Watch initiatives; journalists should be encouraged to include the perspectives of people with mental health disorders and their families and include positive stories about recovery (Wahl, 2003). Reducing the numbers of articles about suicide may be preventative (Stack, 2002) as is use of person- first language and the prominence of articles about suicide – such as not being displayed on the front page or with a headline in large font (Srivastava et al., 2018).

Students were encouraged to choose a more qualitative design than was common in Japanese research, to be more self-directed and to reflect on the enquiry and discovery aspects of research. Through actively engaging as research assistants, students undertook activity aligned with enquiry-based learning to facilitate their learning about both the enquiry process and the content of media in Japan regarding the topic.

These elements of their learning journey are consistent with more active learning espoused in Problem-based learning philosophy. Throughout their learning they also discovered material thought could be the stimulus material that leads to greater appreciation of the needs of people experiencing mental illness and distress.

The students met weekly with their supervisor and following each meeting wrote a reflection on the process of the research. At first their reflections reflected their study grasping the concepts of the study, later they noted their increasing awareness of the need to strictly adhere to study protocols and later took responsibility for taking the research forward. Finally, they reflected that they were able to critically reflect on the process and found the opportunity to think more deeply both novel and stimulating. Media reporting of mental disorders often disproportionately links mental disorders with violence or dangerousness (Diefenbach et al., 2007) and the students began the research with this assumption, but emerged from the process critically evaluating the media reports they evaluated and changing their view on this.

Further Research

Research into the media’s contribution to the deep-rooted stigma about mental disorders in Japan may help to reduce this stigma. Further analysis of the detailed content of each article is also required by a native Japanese article speaker to pick up linguistic nuances. Further research is needed on the coverage of mental health in social forums, television, and fictional media where the indications are that there is more stigmatizing content. Young people are more likely to access social media platforms and may be particularly vulnerable to stigmatizing and misleading content.

CONCLUSIONS

Mental health and suicide are still considered by many to be taboo subjects in Japan and much stigma remains so, it is pleasing that there are indications that the needs of people experiencing mental distress are being reflected in public media in Japan. COVID 19 has had a clear influence on stress and mental health in Japan as in the rest of the world and has undoubtedly affected newspaper coverage. Of concern is the high number of articles featuring suicide given the association of newspaper coverage of suicide and completed suicides. This is particularly critical given that Japan’s suicide rate increased in 2020 and media strategies should be part of any public health strategy to address this unfolding tragedy.

Studies of this type are stimulating to novice researchers and an enquiry-based facilitative style ideally suited to introducing concepts and the research methods to this cohort.