Critical Thinking and Metacognition: Processes and Outcomes within the Learning Cycles

Article information

Abstract

Over the last two decades policy developers across the world have set directions for educational change in pursuit of graduate outcomes that better prepare professionals for the future. Suggestions for radical change in educational practices has meant a need to revisit curricula to question the extent to which graduate outcomes are consistent with contemporary population and workplace needs. Discussion has centred on more process-oriented educational design that aims for learning outcomes especially those acknowledging a need for critical thinking and metacognition as a graduate outcome for professionals. A contextual appraisal of contemporary workplaces i) reveals a need for changes in systems and processes and ii) suggests a need for change in professional practices that in turn impact on educational preparation for practice eg i) movement towards student-centered educational design and ii) encouraging values consistent with ongoing learning in dynamic workplaces. It is the authors’ opinion that educators are at risk of minimising learning processes that lead to critical thinking and metacognition. We suggest that where processes are introduced in learning events, assessment/evaluation tasks have not provided evidence of outcomes consistent with curriculum aims. In the future, curriculum renewal should include interrogation of appropriate assessment tasks that provide evidence of outcomes that reflect ability to think critically and reflect on processes in a manner consistent with metacognition. Research that focusses on the nature and extent of those outcomes is also warranted.

INTRODUCTION

This paper aims to reflect on i) the scholarly reports within presentations at the 2021 symposium entitled ‘PBL in Education transition: ‘New trends and challenges’ (Cheju Halla University – CHU, 2021); ii) research initiatives sponsored by the International Society for Problem-based Learning at CHU (www.ejpbl.org). At the symposium many new people joined old friends who have supported the PBL initiatives in Jeju, South Korea, over the last two decades. Research sponsored by CHU has explored initiatives for educational change.

The authors examine the extent to which change agendas have encouraged approaches to learning advocated by policy directives across the world (WHO, UNESCO), especially in relation to introducing and assessing the full suite of abilities that professionals need in the contemporary environment. It is suggested that the introduction and assessment of critical thinking, reflection on practice that leads to metacognition need greater focus within process-oriented curriculum implementation.

THE DEMAND FOR EDUCATIONAL CHANGE

Articles submitted to this journal report that policy developers across the world have set directions for educational change in pursuit of graduate outcomes that better prepare professionals for the future (Park et al, 2020;Zumbach et al, 2020;Byun, 2020;Cho et al 2021). Byun (2020) cited the World Economic Forum (WEF) proceedings where in 2017 it was suggested that ten skills were required to thrive in the Fourth Industrial Revolution: Complex Problem Solving, Critical Thinking, Creativity, People Management, Coordinating with Others, Emotional Intelligence, Judgment and Decision Making, Service Orientation, Negotiation, and Cognitive Flexibility. Advocating for change, Byun argued that application of a wide range of knowledge and the acceptance of new knowledge, is a necessity in problem solving, an ability central to the roles and functions of various professionals within society.

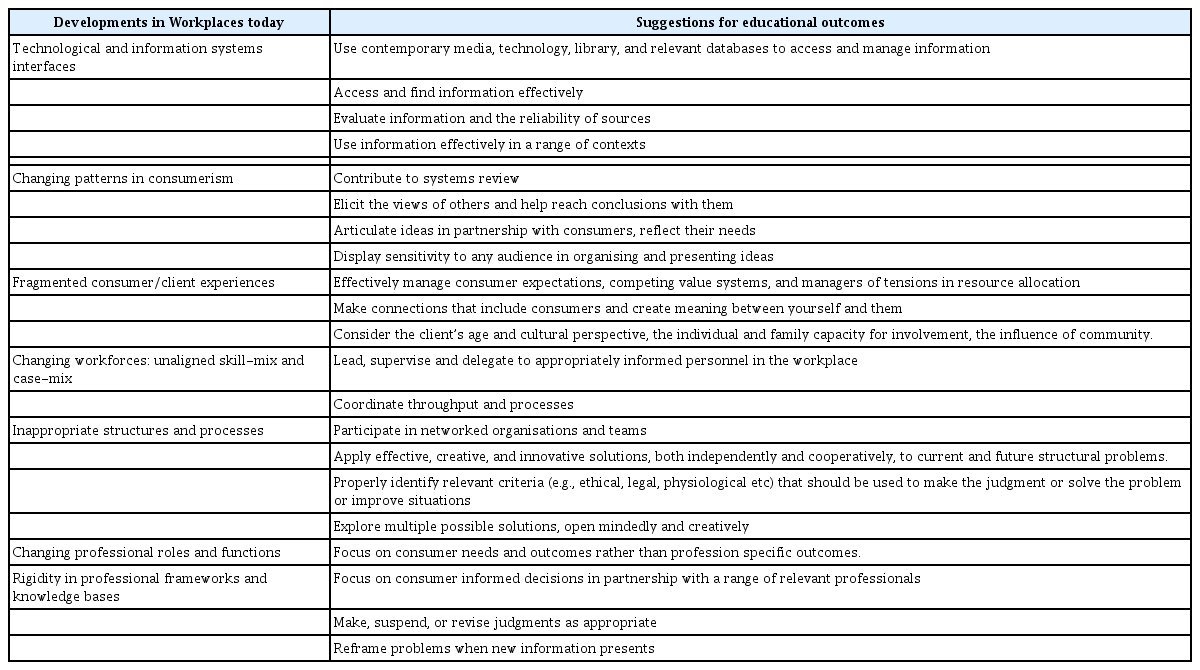

A scan of formal organizational websites demonstrates responses to policy directions; these confirm the need for the change agenda. Organizations such as the Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER), the United Nations (UNESCO), and the national policy frameworks have outlined desirable changes on government websites: all have focussed on higher and further education. For some like the World Health Organization (WHO), directives suggest radical change in educational practices and questioning around the extent to which graduate outcomes are consistent with contemporary population and workplace needs (Table 1). Policymakers are telling us that now is the time to re-assess the educational landscape from multiple perspectives e.g., re-alignment of roles of professional in practice relevant to population needs, addressing social, ethical, legal issues and respond to significant changes evident in educational policy (suggesting more student centered and blended learning), research & consultation (a focus on translational designs).

ASPIRATIONS VERSUS OUTCOMES

Scholarly articles in the journal report on more process-oriented educational design that aims for learning outcomes such as evidence of the ability to problem solve. However not many refer to a higher order need for critical thinking and metacognition as a graduate outcome for professionals. The authors therefore asked themselves whether the educational philosophy and design reported on within scholarly papers in the journal and presentations at the symposium align with the aspirations of policy makers for graduates from the professions who can deal with novel situations and competing tensions.

As shown in Table 1 a contextual appraisal of contemporary workplaces reveals a need for changes in systems and processes and but also suggests a need for change in professional practices; this in turn impacts on educational preparation for that practice. For example, the need for movement towards more practice-based and client/student-centered educational design. Curricula need to provide evidence of graduate outcomes that equip professionals with a suite of abilities to manage clientele in a manner consistent with the desired changes (UNESCO, 2019;Byun, 2020). There is also a need to encourage professional values consistent with ongoing learning in workplaces as new initiatives such as technological innovation emerge.

Table 1 shows some suggestions for desirable changes in educational outcomes that reflect competent graduates who are confident and competent in contemporary workplaces.

EVIDENCE OF CHANGE INITIATIVES

In topics chosen for research sponsored by the Halla/Newcastle Center we have seen project reports that

• Showcase innovation in educational processes for older clientele in communities

• Describe efforts to revise curricula in ways that mirror government policy

• Demonstrate interest in PBL methodology from a range of disciplines and cultures

• Compare students’ and teachers’ experiences with PBL

• Describe learner-oriented methods

• Apply online PBL to ethical dilemmas

• Seek to develop suitable evaluation questions for ‘non-tact’ classes

• Apply process-oriented methods to English language development.

Some research translated into scholarly articles while others wrote reports about

• Their quest for more insight into components of PBL (Cho et al, 2021)

• The need to change educational processes for optimal learner impact (Zumbach et al, 2020)

• The drive to feature contexts of practice in learning for various disciplines (Treloar et al, 2019)

• Professional development for educators (McMillan & Little, 2019)

• Virtual and high-fidelity simulation in learning events (Park et al, 2016)

• Greater student autonomy as sometimes seen through ‘flipped’ learning (Yoon et al, 2017; Chung & Lee, 2018; Jung & Hong, 2020)

• The advantages of engaging with technological change (Murakami et al, 2021)

• Use of projects as learning events involving problem-solving (Chiang et al, 2017).

PBL: DESIGN PRINCIPLES

We revisited the principles underpinning PBL and questioned the extent to which the initiatives lead to the development of a full suite of abilities suited to meeting the demands of workplaces in the contemporary global environment. We were asking ourselves whether the PBL design/s aligned with the aspirations of policy makers for graduates from the professions who can deal with novel situations and competing tensions such as those outlined above. One example of funded research that meets the criteria, centered on an evaluation of a ‘Flipped Learning’.Yoon et al, (2017) showed how the use of MOOCs supported more active learning: Students expanded their information literacy, were more active and autonomous and were caused to apply concepts and theory to scenarios based on actual practice. The latter encouraged a deeper approach to learning when compared to teacher-centric classes and encouraged interaction with groups of peers. Yoon et al used PBL as an educational methodology and philosophy and as such goes beyond a teaching and learning strategy. They put the student at the centre of the learning process and acknowledge that each learner will make their own meaning from their educational experiences based on their life and professional experiences. It is, however, the role of the teacher to assist the students to come to that meaning through a thorough examination of the processes used to arrive at their understandings.

EDUCATION FOR PRACTICE

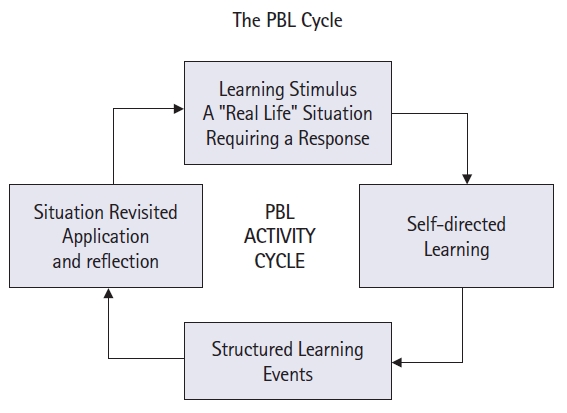

In professional education (undergraduate or postgraduate) learners are presented with problematic situations from their professional practice or discipline; they analyse, investigate, and propose responses to relevant stimulus material involving situations that require a resolution. This can be described as the Activity Cycle in PBL This should always be in the context of the professional practice or discipline (PROBLARC, 2000;Park et al 2013, 2016) (Figure 1).

One of the essential tasks of the teacher then, is to make explicit what is involved in those thinking processes in the context of the discipline or professional practice. These processes involve situation analysis, knowledge application and decision making, but most importantly include “thinking about” how those processes are informed by the nature of the discipline or professional practice and the assumptions that are embedded in the discipline or practice. In the experience of these authors, many learners or indeed professionals have not experienced this level of interrogation of their discipline or professional practice. In PBL this interrogation can be described as the Metacognitive Cycle (PROBLARC, 2000; Conway and McMillan, 2019) (Figure 2).

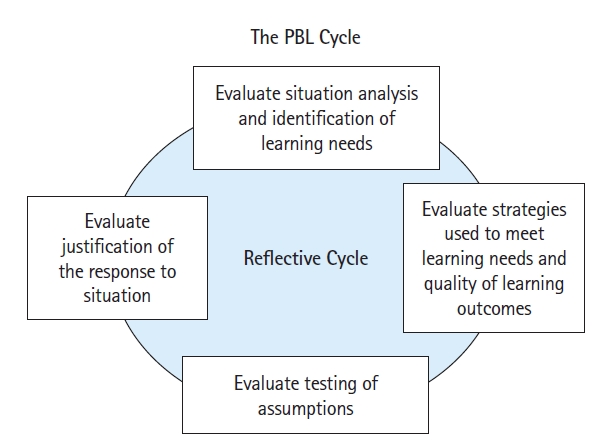

A third critical component in PBL is the act of reflection (Boud, 2009) which involves not only reflection on the learning outcomes (which may be intentional and/or unintentional) but also on the learning processes and their effectiveness. The reflection should always be informed by self, peer, and teacher evaluation. This is described in the PBL Reflective Cycle (PROBLARC, 2000) (Figure 3).

Proponents of the process-oriented educational design argue that the full potential of process-oriented curriculum design such as PBL will only be realised when all three cycles are deployed systematically and simultaneously in the context of practice and when the educators who construct and conduct the learning experiences, have themselves analysed and made explicit the essence of their discipline or professional practice (PROBLARC, 2000) (Figure 4).

EDUCATION FOR PRACTICE

The authors of this paper all have a higher education professional focus across many disciplines but predominantly on nursing. They note that when nursing moved from a vocation to a profession, there was much debate and introspection in the nursing literature as to what defined and differentiated nursing practice from other health professions. The Australian College of Mental Health Nurses in Australia recognized this process of interrogation of actual professional practice was essential for their discipline aim to design programs that prepare graduates for contemporary practice (ACMHN, 2016).

When designs such as PBL were applied to nursing education in Australia, some of the existing practices such as the nursing process were subjected to challenges. The successful nursing programs not only analysed the nature of the practice but made the thinking processes explicit and acknowledged that while knowledge should be derived from theory integrated with practice, knowledge acquisition needed to be based on evidence from sound research. Many also argued that knowledge that comes from the lived experience, which when properly critiqued, can also inform practice. These authors propose that when PBL programs apply the three cycles as a systematic learning strategy, the learner develops the ability to think critically within their professional practice and has the potential to apply critical thinking as a citizen and as person, clearly a desirable outcome of higher education. Savin-Baden (2000) describes five models of PBL that progress from Model 1 where students are passive receivers of knowledge in order to solve problems within a discipline to the acquisition of skills as well as knowledge to undertake practical action in the workplace (Model 11) to Model 111 where students synthesise knowledge and skills across disciplines and finally to Models 1V and V which require students to be independent thinkers, applying a critical stance to learning through the interrogation of frameworks and the exploration of underlying assumptions and belief systems. Savin Baden argues that only models 1V and V have the potential to achieve critical thinking and “critical contestability” (p176). These authors suggest that if the Activity Cycle is used alone, the potential for full interrogation of the professional practice is unlikely to be achieved. When all three cycles are incorporated within the learning process simultaneously, the potential for critical thinking and critical contestability as learning outcomes enabling practitioners to develop and defend their own conceptual framework of practice is more likely to be achieved. While the three cycles guide curriculum developers and facilitators in the process component of PBL curricula, the students need to learn and apply the processes routinely as they work through practiced -based situations. Conway and McMillan (2010, p364) provide a set of questions that facilitators can use to guide learning and reflection on the processes of learning.

Another desirable graduate outcome often identified is creativity. This was highlighted in many of the 2021 symposium presentations. Graduates need to be able to use enquiry processes to deal with novel situations but grow as innovators as well as competent and confident practitioners. The thinking processes involved in creativity may focus more on the solutions and synthesise new constructions, arrangements, patterns, and responses. The balance between critical thinking and creativity will be different for different fields of practice.

PROCESS-ORIENTED CURRICULA IN CHANGING TIMES

Our reflection on ‘enquiry- or practice-based’ philosophy and methodology reminded us of the learning process aims that is, for ‘successful implementation’ one needs to

• offer learning events that highlight relevant, evidence-based practice

• design student-centered learning events placing students in professional roles from the start

• cause students to think like the professional they want to become

• encourage information literacy & self-direction in learning

• provide evidence of outcomes consistent with the methodology eg metacognition, collaboration/interprofessional teamwork

• provide evidence of outcomes consistent with methodology

• model ability to work in a team

• build capacity to assume leadership roles irrespective of discipline base.

However, recent aspirations to make access to education more equitable and the demand for greater information fluency, initiated movement towards more blended modes of delivery and in some instances programs solely reliant on the on-line mode of delivery. The COVID19 pandemic was a catalyst for even greater reliance on technology but also highlighted the complexities of aligning the PBL philosophy and methodology with a changing learning and teaching environment. Rapid responses to pressures to manage the challenges might have led to abandonment of the central tenets of sound educational practices. It was difficult for both students and teachers to accommodate the concept of ‘classroom events’ in the online environment. Larger class sizes have become the ‘norm’ as policy shifts highlighted the notion that education for all was important in an informed society that was ready to embrace change that was inevitable.

The numerous changes in education environment including but not limited to the online environment, pose challenges for educational designers who must revisit the ambitions for the core aspirations of policymakers for graduates who have honed their ability for Critical Thinking (CT) and metacognition. There are also challenges for curriculum designers around achieving a reasonable level of integration of supporting disciplinary concepts to the core of profession-specific discipline. Given the policy imperatives to meet the challenges of society and prepare graduates for the future we are revisiting one of the central tenets of action-oriented approaches to learning that equips students to deal with novel situations.

CONTEMPORARY ASPIRATIONS FOR GRADUATE OUTCOMES

A recent UNESCO consultancy identified five pillars to guide Artificial Intelligence (AI) and those involved with educational design and implementation. Of interest here is the demand for further adaptation around critical thinking:

• data awareness, manipulating, visualizing large amounts of data

• understanding randomness and accepting uncertainty

• coding and computational thinking that foresees skills to solve problems through algorithms

• Critical thinking as adapted to the digital society

• Reconsideration of key concepts such as intelligence, experience, creativity, ‘the truth’ (UNESCO, 2019)

GRADUATE OUTCOMES

Statements of ‘Graduate Attributes’ samples from websites about university programs across Australia show the following as common to many curricula preparing professionals for practice

• Thinkers who are curious, reflective, and critical

• Innovators who have ideas and can realize their dreams

• Citizens who engage in socially and culturally appropriate ways to advance individual, community, and global well-being

• Communicators who can create, exchange, impart and convey information and ideas

• Leaders who display and promote positive behaviors and aspire to make a difference, acting with integrity, are receptive to alternatives and foster sustainable and resilient practices.

Central to all professional programs is the aim to cause graduates to think more critically when faced with the inevitability of situations in workplaces that are new to them. Developing students’ critical thinking (CT) skills is facilitated through metacognition (Magno, 2010). The relationship between metacognition and critical thinking was initially put forward by Schoen (1983) who explained that “… a successful pedagogy…(serving) as a basis for enhancement of thinking will have to incorporate ideas (on) the way in which learners organize knowledge and internally re-present it and the way these re-presentations change and resist change when new information is encountered” (Schoen 1983, p. 87).

In Schoen’s explanation, enhancement of knowledge is referred to as critical thinking and the process of organizing knowledge a factor in metacognition. But definitions of critical thinking vary widely - determining what critical thinking is to a particular discipline and to what extent it is required to practise competently is difficult. For example, despite the enormous amount of literature suggesting critical thinking is essential in nursing (Conway & McMillan, 2018), fundamental assumptions about the nature and purpose of critical thinking in a range of disciplines have yet to be addressed.

When exploring the relationship between CT ability and professional practice in learning scenarios one needs to ask:

What evidence is there that professionals need to engage in CT or that CT underpins effective decision making in any professional group? To what extent, if any, does CT ability contribute to professional success?

To what extent is the ability to think critically essential to professional competence and confidence? Is CT ability enhanced or restricted by professional socialisation?

Therefore, when developing CT strategies for learners we also need to ask does it develop as a maturational process, or how can CT skills be taught? If these skills can be taught, what further educational strategies are appropriate to enhance the development of critical thinking in the professions? Which educational strategies purport to enhance critical thinking in the education literature, and are educators using these in teaching and learning situations and what are the strengths and limitations of these?

Considerable emphasis has been placed on the ability to problem solve and make effective judgements within various professional contexts of practice. However, often there is no clear requirement for, nor definition of, critical thinking other than the ability to problem solve.

MEASURING CRITICAL THINKING

If one accepts that critical thinking ability is essential for any professional practice, there needs to be a way of determining this ability. An operational definition developed through collaborative focus groups suggested that: “…critical thinking is the repeated synthesis of relevant information, examination of assumptions, identification of patterns, predictions of outcomes, generation of options and choice of actions with increasing independence” (Jacobs et al, 1997). Such a definition implies that critical thinking is a process that develops over repeated exposure to situations; this justifies longitudinal studies to evaluate critical thinking.

CRITICAL THINKING FOR THE 21ST CENTURY

Over the last two decades, across the world, CT and problem-solving capabilities remain as highly valued employee competencies. Some examples provided by Tregoe (2021) are as follows:

• It is now clear that learning processes that involve critical thinking, lead to better outcomes for life and work

• CT is a skill that can be taught and learned and persists over time.

• Determining which information is relevant and significant leads to greater understanding of the best way forward in any situation.

• In organizations, when problems go unresolved, decisions are made based on limited information, taking risks when there is a lack of ‘thinking patterns’ clarity. This increases the potential for adverse events.

• Quality in consumer or customer service is reliant on problem solving (root cause analysis) in a timely fashion.

• Waste reduction is also reliant on the production of meaningful data that informs processes and actions.

• Information Technology (IT) and other technology is evident in virtually everything we do in 2021; CT skills help problem solvers to unpack complex problems into more manageable ‘chunks’ that can be dealt with effectively and in a cohesive way (Tregoe, 2021).

ASSESSMENT/EVALUATION TASKS

It is not enough for curriculum developers to provide objectives for students to engage in CT. Their assessment/evaluation tasks must provide evidence of outcomes consistent with that objective. The Australian Council of Educational Researchers (ACER) provided the following for consideration by educators when designing assessment tasks that provide evidence of a student’s ability to think critically:

“Critical thinking is typically assessed within content areas. For example, students analyse evidence, construct arguments, and evaluate the veracity of information and arguments in relation to disciplinary core ideas and content.

Assessing students’ level of sophistication with critical thinking skills and dispositions requires close attention to the nature of the task used to elicit students’ critical thinking”.

Assessment tasks and criteria must be thoughtfully designed and structured to

(a) prompt complex judgments

(b) include open-ended tasks that allow for multiple, defensible solutions, and

(c) make student reasoning visible to teachers (Evans 2020 in ACER, 2021).

PBL: REFLECTION ON THE CYCLES AND GOALS FOR METACOGNITION

Given the processes outlined in the figures provided above, educators need to ask additional questions of their learning and teaching approach:

• Was the goal for metacognition clear to students and educators?

• Do enquiry processes allow students to think, think twice and think again about new ideas and situations?

• Are learners able to actively use knowledge acquired in learning events?

• Can students rectify situations when they haven’t understood concepts?

• Is there evidence in evaluation/assessment tasks showing goals/desired outcomes were met?

• Is reflection on learning processes and outcomes a feature in assessment tasks?

The authors acknowledge that there are broader issues that faculty members are presently dealing with, especially given the uncertainty in student and academic experiences as the pandemic continues to impact on higher and further education. However, there are other factors impeding the realization of goals for critical thinking and metacognition as a graduate outcome. These include limited explicit valuing of student-centred learning and a lack of assessment/evaluation criteria centred on competencies consistent with PBL aims for metacognition. Limited Professional Development based on values consistent with PBL might arise from differing conceptions of practice and learning. Hence there is some difficulty in devising measures of quality in educational experiences when stakeholders express diverse needs and demands. This might also contribute to a failure to cause students to reflect on “moments” in significant learning events.

THE WAY FORWARD: RETHINKING CURRICULUM DESIGN

Educational processes are essentially about management of change and thoughtful consideration of when to refresh, renew or abandon curriculum strategies. Mechanisms for change must always be based on student needs, but the following are key to successful change: Look for links: Consistency between intentions versus outcomes; Focus on assessment tasks and criteria; Improve skills in reflection; Use Professional Development that reflects values consistent with PBL; Employ Educational Designers for learning events, especially on-line events.

CONCLUSION

Recent global policy has informed curriculum developers across the world. Funded research within the PBL Center and scholarly articles in this journal have focussed on educational change in pursuit of graduate outcomes that better prepare professionals for the future.

For change initiatives to be consistent with policy directions, curriculum implementers need to question the extent to which evidence of graduate outcomes is consistent with a profile of abilities that matches contemporary population and workplace needs. Discussion has centred on a demand for more process-oriented educational design that aims for learning outcomes especially those acknowledging a need for valuing critical thinking and metacognition as a graduate outcome for professionals.

After examining change initiatives reported on above , it is the authors’ opinion that educators remain at risk of minimising learning processes that lead to critical thinking and metacognition. Further, we suggest that where such processes are introduced in learning events, assessment/evaluation tasks have not always provided evidence of outcomes consistent with curriculum aims. In the future, curriculum renewal should include interrogation of appropriate assessment tasks that provide evidence of outcomes that reflect ability to think critically and reflect on processes in a manner consistent with metacognition. Research that focusses on the nature and extent of those outcomes is also warranted.

Notes

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.